The Light at the End of the Dock

What can be learned from F. Scott Fitzgerald's time in Hollywood

I’m writing from Los Angeles, where, despite the fiery protest images you may have seen recently, things are by and large peaceful and business as usual. Though the rage and fury seen in the photos could, I guess, reflect how many of us feel about masked men coming in and tearing away members of our beloved immigrant community.

As I’ve said before, LA has been no stranger to disruptions and instability lately. Some occur naturally, but this one, like others, was definitely man-made.

On a seemingly unrelated topic, I recently found myself wondering about the time that F. Scott Fitzgerald spent here. I always remembered that it didn’t go that well for him, but I didn’t know much beyond that. What was it actually like for him?

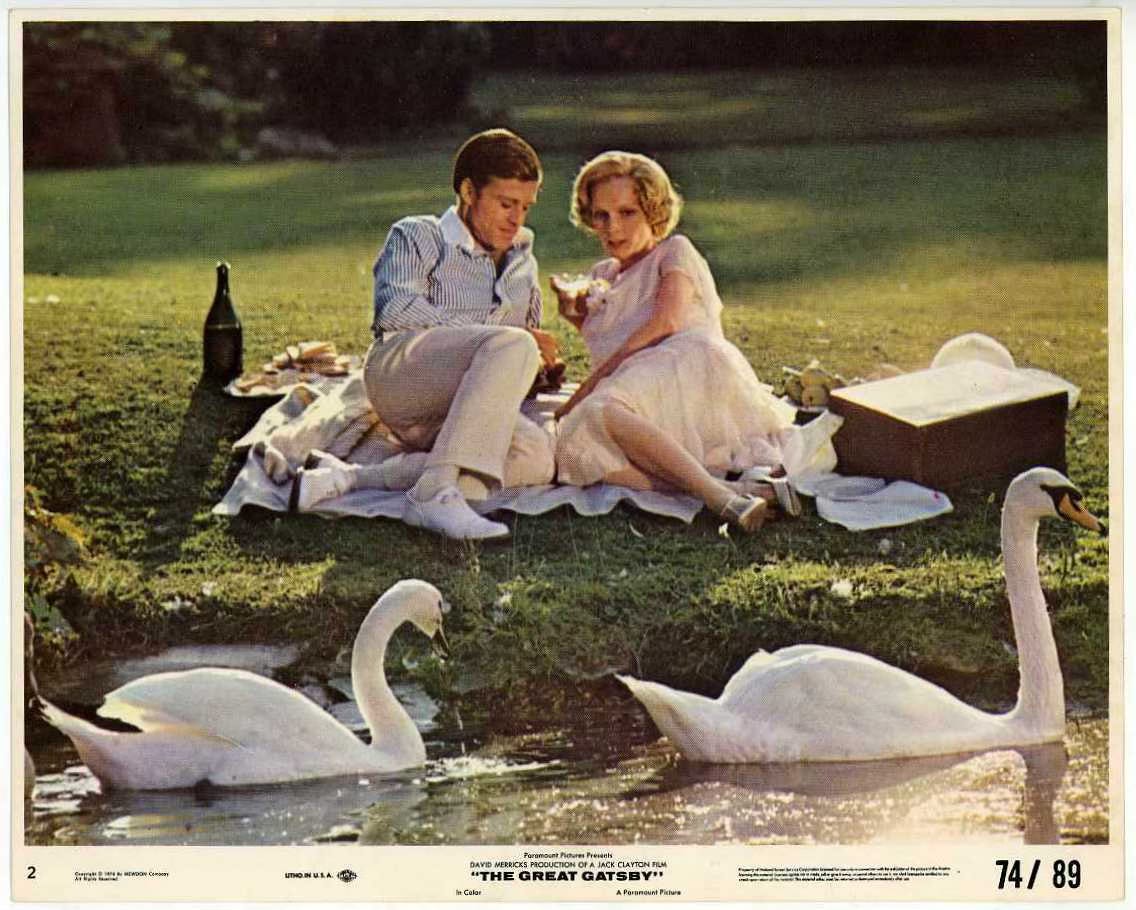

The Great Gatsby turned 100 this year and is considered by many to be the Great American Novel. It may be the greatest American Dream story we’ve ever had. One would think that if you put Fitzgerald in Hollywood, “the land of dreams,” we may have ended up with the Great American Movie as well, but of course that isn’t the case.

I didn’t know, for example, that he had a brief, two-month stint here years prior, spent mostly partying. I didn’t know that the few years he lived here were actually the last years of his life.

Then I heard about The Pat Hobby Stories. How is there a whole book of his I’d never heard of? Weren’t there only about four novels of his in total?

It turns out Pat Hobby is a character he created while living here, somewhere in the realm of parody or satire, a hack screenwriter. Fitzgerald himself came to Hollywood under a lucrative contract with MGM but was unable to produce much to their liking and ended up losing it. Is Pat Hobby a version of himself, a sort of self-mocking, or is it a way of creating distance for himself from that image? Or is it mocking something else entirely, maybe the system itself?

He wrote it in the form of short stories that he intended to turn into a single work, and he was writing it alongside The Last Tycoon, a novel about a producer in Hollywood, both unfinished at the time of his death.

The editor of The Pat Hobby Stories believes these stories have been overlooked because of a “pathetic fallacy: these stories are about a hack, ergo these stories are hack work.”

Here Pat empathizes with authors who don’t fit into the Hollywood system:

“Authors get a tough break out here,” Pat said sympathetically. “They never ought to come.”

"Who’d make up the stories—these feebs?”

“Well anyhow, not authors,” said Pat. “They don’t want authors. They want writers—like me.”

Throughout most of his career writing, Fitzgerald’s main representatives had been Maxwell Perkins (editor) and Harold Ober (agent), who had both gone to great lengths to keep him published and paid. But after spending money out of their own pockets, both had drawn a line with the Pat Hobby stories. The editor of the volume published by Scribner years later suggests that Fitzgerald pushing these stories on them may explain their annoyance—and why the stories were ignored for so long.

The stories were, however, being published serially in Esquire, which I believe was his main form of income in those years. At one point, he suggested to his editor to publish it under a pseudonym. “I’m awfully tired of being Scott Fitzgerald anyhow as there doesn’t seem to be so much money in it.” He went on to say, “I’d like to find out if people read me just because I am Scott Fitzgerald or, what is more likely, don’t read me for the same reason.”

America had changed from a time of abundance—gin-drinking during the jazz age, to which he’d tied himself by writing The Great Gatsby—to a time of scarcity, with a recession and a war looming. According to a gossip columnist he was seeing at the time, Sheilah Graham, in an act of desperation he drunkenly asked passing strangers if they still remembered his name.

The stories from his last years in Hollywood do sound desperate—money wasn’t easy, he wasn’t achieving the sort of success as a screenwriter that he enjoyed as a novelist, he worried about being forgotten about—but I believe that something else was going on too. I think he was fascinated by the place.

And I think it can be seen in the stories of Pat Hobby. He’s constantly scheming to get on the studio lot, where he’s rarely employed. But he still wants to be there as to be in the vicinity of those who are hiring.

Fitzgerald delights in Hobby’s schemes getting foiled. If he, as a way of staying on the lot, escorts foreign tourists through fully functioning sound stages, he would inevitably wind up in front of blinding lights and cameras with a director shouting angrily from somewhere in the dark.

Hobby constantly tries to get a seat at the lunch table with the executives and producers, the big shots who might give him a shot at his next job, but usually winds up seated with younger writers or the “secretaries and extras” a few tables over.

In the stories, Pat Hobby spends more time remembering fifteen years back when he owned a pool in Beverly Hills than he does writing. In recent days with studios being sold and downsized, there can be a similar sense of looking back to bygone eras while also wondering what’s to come.

It’s unclear how much of this has-been writer Fitzgerald saw in himself, but there are clear differences: Fitzgerald didn’t have a slow demise in Hollywood for 15 or 20 years straight like Hobby. He did, however, wind up there after years of partying with Zelda in New York and the Hamptons.

And at this point in his life, there’s no doubt that he was struggling financially. He was paying for Zelda’s treatment in a psychiatric institution in Asheville, NC. You could say he was someone, as the writer George Saunders put it, “whose grace suffered under the toil of needing to earn a living.”

But I still think he must have been fascinated by Hollywood—all of the different walks of life forced into one small space, everyone vying for a bigger paycheck, a better credit, all united with the common goal of making a movie.

As the actress Shirley MacLaine once described it, “Blue collar, white collar, no collar, money, critics, out-of-control emotionalism. All of this goes on, and every bit of it is respected on set.” I imagine this would be catnip to a writer like Fitzgerald.

The biggest difference between writing novels and working on movies has to be the leap from working alone to working in collaboration with a large group of people. I think it’s rare if a writer can make that jump and have as great an impact on the film world as they did writing books. As the director Billy Wilder said about Fitzgerald’s work in Hollywood, it was like that of “a great sculptor who is hired to do a plumbing job.”

At one point, Fitzgerald expressed regret in getting involved in movies in a letter to his daughter. “I wish now I'd never relaxed or looked back,” he wrote, “but said at the end of The Great Gatsby: I've found my line—from now on this comes first. This is my immediate duty—without this I am nothing.”

I learned something recently about his life that changed the way I think about The Great Gatsby. While in college at Princeton, he dated someone named Ginevra King, who was, like him, from the Midwest except that she was from a higher income-level family. She was a “debutante” or “socialite” in Chicago, whereas his family in St. Paul, MN was considered more middle class.

Their meeting at an Ivy League school on the East Coast already parallels the plot of The Great Gatsby, which mostly features Midwesterners striving for success or a foothold out East, particularly Long Island.

Ginevra King was socially ambitious, whatever that may mean in that time period, but enough so that we know she got kicked out of Princeton, and the headmistress called her “an adventuress.” That effectively ended her relationship with Fitzgerald, as she moved back to Chicago. Heartbroken, he then dropped out of school within the year and enlisted in the army.

But seemingly, the determining factor in ending their relationship wasn’t her getting kicked out of school and moving away—it was their class status.

Her family never approved of Fitzgerald, and on one notable occasion, while he was in their home, he overheard her dad say loudly, “Poor boys shouldn’t think of marrying rich girls.” That’s a moment he wasn’t likely to forget.

Just like how Pat Hobby seems to be the stand-in for Fitzgerald in The Pat Hobby Stories, the narrator of The Great Gatsby, Nick Carraway, would in many ways seem to parallel Fitzgerald as well. He’s the narrator, after all.

But it’s Gatsby who may more closely resemble Fitzgerald. Also from the Midwest, he’s achieved more financial success than Nick (which Fitzgerald had also done), making him appear to fit into the culture of the Hamptons better.

And the elusive green light he stares at night after night is on the dock of Daisy Buchanan. She, like Ginevra King, is from upper-class Chicago and living that life, just out of reach for Gatsby.

Gatsby uses Nick (who is Daisy’s cousin) to try to get closer to her, but she ultimately decides to stay with her husband, who like her is also from the upper class. Notably, she decides this when she realizes that Gatsby built himself up by bootlegging liquor (ie., not from the upper class.)

In other words, all of the partying lifestyle aside, is this book ultimately about the impossibility of breaking class lines? In America, we tend to think that anybody can achieve anything, so long as we work hard enough, that we’re not like other cultures with rigid class structures.

But Fitzgerald learned a really hard lesson when his heart was broken by Ginevra King, and I don’t doubt that he would want to impart that to an American audience.

Gatsby achieved success but was exposed as being from a lower class and then ultimately murdered by the upper-class husband of the woman he loved. This is not a hopeful message. It’s not a “pull yourself up by your bootstraps and everything will work out okay” story. In the end, Fitzgerald has most of his characters pack up their things and leave the East Coast, as they now feel they will never actually fit in there.

But I would say it’s still a story about striving, in the best sense. As Nick says about Gatsby in the opening pages, “There was something gorgeous about him, some heightened sensitivity to the promises of life.” There’s no higher praise in Fitzgerald’s world than that. And if the characters can’t ultimately have what they want, it may be sad, but it’s not their fault. That’s just how it is.

Fitzgerald, for his part, was nearly an exception to this rule. He achieved runaway success with his writing, and he relished in it. He shot through the class barriers like a meteor but ultimately came down again on the other side. The Great Gatsby was both his vehicle out of the middle class and a prediction that it wouldn’t last.

I wonder if one of the things he liked about LA was that, despite large gaps in wealth, there’s less of the old-money rules of the East Coast. It’s more of a cultural free-for-all. Even still, if one finds themself thinking about life on the other side of the tall hedges too much, it seems best to remember his warning about the rigidness of class barriers, even in free-market America.

Fitzgerald died of a heart attack unexpectedly while still living in LA. The night before he died, he went to see a show at the Pantages Theatre and felt dizzy, stumbling out to the street. “They probably think I’m drunk,” he said.

Though his years of hard drinking and health issues might have made his death seem not unexpected, I’m sure it still came as a surprise to him. I’m sure he wanted to finish The Pat Hobby Stories, just as he wanted to finish The Last Tycoon.

I know there’s something tragic about Fitzgerald’s time in Hollywood, but I also think there’s something optimistic in the scrappy, enduring nature of what he saw in it.

When Pat and a famous actor from an earlier time get thrown in prison for a drunken argument in the streets, Pat insists that the two had met years before on set. The actor has no memory of it, and the policeman only cares about meeting the actor he’s seen on screen. The two ignore Pat, as he continues to make his case from within a cell.

But it’s Pat who gets let out first when another policeman actually listens to his story. In it, he tells of the actor who played a war hero in the movie but behaved like a coward on set.

Outside the policeman asks him if that was true. “Sure, it is,” Pat said. “That guy needn’t have been so upstage. He’s just an old-timer like me.”

Some may read these stories and think that Pat Hobby is F. Scott Fitzgerald and vice versa. But there’s a character who shows up a couple times only briefly who seems like a closer fit. He’s a novelist who’s been commissioned to work on movies, and every-time we see him, he’s angry that someone has broken a promise or compromised his work. Unlike Hobby, who would happily put his name on anything whether he wrote a word of it or not, the author is trying to get his name off of scripts. Now that sounds more like Fitzgerald to me.

After much discussion with my colleagues in academe, I re-read The Great Gatsby, one of my favorite books. He was telling the America of his era. How call African Americans Negroes anymore.? I can go as many seem to suggest the current administration is wanting to return to that era.